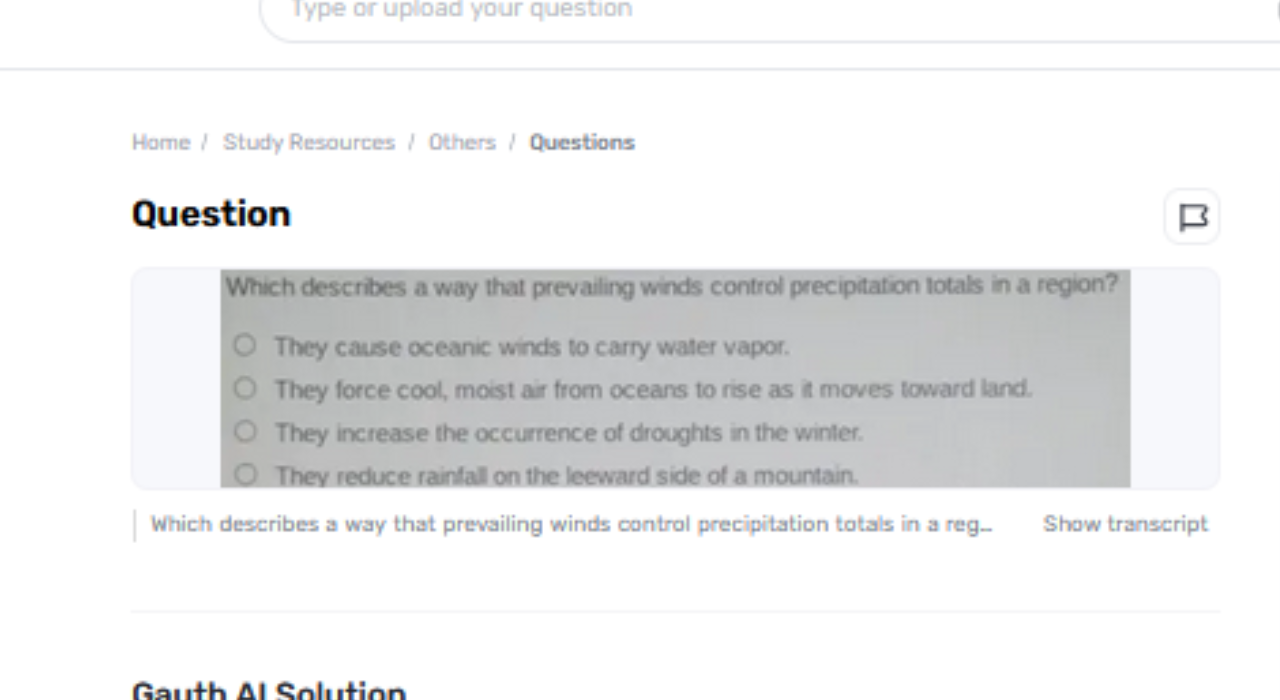

In the image above there are two wearables. One is Fitbit’s recently released Charge 5, a $179.95 fitness tracker designed to measure everything from your heart rate to your sleep and even your skin temperature. The other is Amazon’s new $79.99 Halo View fitness tracker, which Amazon says can measure everything from your heart rate to your sleep and skin temperature. Ten points if you can tell me which is which.

The Halo View was just one of a host of new devices announced by Amazon at its now annual fall hardware event this week. But while many of Amazon’s new products feature completely original designs and features, like its cute Astro “home robot” or Ring-branded home surveillance drone, there were a handful that bear a striking resemblance to preexisting products.

Take Amazon’s new $59.99 smart thermostat, which works with Amazon’s voice assistant Alexa, and promises to detect when you’re home and adjust the temperature accordingly. That’s very similar to what other Alexa-enabled thermostats like the $250 Ecobee smart thermostat offer, but at a fraction of the price. Not to mention Amazon’s design is also similar to a preexisting smart thermostat produced by a company called Tado (which itself retails for the equivalent of around $240).

Not every smart thermostat needs to look completely original or have a unique set of features (after all, there’s only so much a thermostat can do). But the announcement of Amazon’s own Smart Thermostat comes just months after The Wall Street Journal reported that Ecobee had been nervous about sharing additional data with Amazon, in part due to fears that this data could help it launch competing products, as concerns that it could harm consumer privacy. Ecobee was reportedly told that failing to provide this data, which would send information to Amazon about the device’s status even when a customer wasn’t using it, could risk the company losing its Alexa certification for future models or not be featured in Prime Day sales.

In response to The Verge’s enquiry, Amazon said it hadn’t used data from any other Alexa-connected thermostats to design its Smart Thermostat. It said the device had been co-created with Resideo, a company that has also worked on Honeywell’s Home thermostats, and that Ecobee continues to be one of its valued partners.

Meanwhile, Amazon’s new Halo membership features look like obvious competitors to MyFitnessPal. Halo Nutrition is designed to help users find recipes and cook food that fits their dietary needs, similar to the Meal Plans feature MyFitnessPal already includes as part of its premium plan. There’s also Halo Fitness’ guided workouts, similar to the self-guided routines from MyFitnessPal. But Amazon’s health subscription is a lot cheaper than MyFitnessPal’s premium tier. Amazon includes a free year of its Halo membership services with the purchase of its new Halo View fitness tracker, and it retails for $3.99 / month thereafter, which is less than half the price of MyFitnessPal’s $9.99 premium tier.

When we asked Amazon about these similarities, it said it had not copied other companies, and that its Halo service includes unique features not available with other fitness trackers.

Responding to questions from The Verge, Amazon said it’s “pioneered hundreds of features, products, and even entirely new categories” throughout its history. “Amazon’s ideas are our own,” the company said, citing products such as the Kindle, Amazon Echo, and Fire TV as prominent examples of its original inventions.

I’m not trying to claim that Amazon is breaking any rules with these products. There are only so many ways you can design a screen that straps to your wrist and shows you your heart rate — even if this one has clear Fitbit vibes — or a panel that attaches on your wall to control the temperature. Even complicated devices like smartphones have seen their designs gradually converge over the years, a process not helped by the fact that many manufacturers are using components supplied by the same small handful of companies.

But the similarities look cynical coming from Amazon, which has been criticized for ripping off the designs of products sold on its platform and then undercutting them on price. Earlier this year, bag and accessory manufacturer Peak Design drew attention to the startling similarity between its $99.95 Everyday Sling and Amazon Basics’ $32.99 Camera Bag, for example. Amazon’s version of the bag has since been discontinued, the company told The Verge.

Amazon’s cloning of the Peak Design bag wasn’t an isolated incident, either. In 2019, striking similarities were also pointed out between the $45 shoes produced by Amazon’s 206 Collective label and Allbirds’ $95 equivalent. The similarities prompted Allbirds CEO Joey Zwillinger to respond in a Medium post saying that he was “flattered at the similarities that your private label shoe shares with ours,” but politely asked that Amazon also “steal our approach to sustainability” and use similarly renewable materials. Amazon said that the shoe has also since been discontinued, but that it continues to offer similar styles. Amazon also said its original design did not infringe on Allbirds’ design, and that the aesthetic is common across the industry.

Or what about the Amazon Basics Laptop Stand that Bloomberg reported on in 2016, which was launched at around half the price of Rain Design’s (at the time) bestselling $43 model? Harvey Tai, Rain Design’s general manager, said that the company’s sales had slipped since Amazon’s competing model appeared on the store, although he admitted that “there’s nothing we can do because they didn’t violate the patent.”

Copying and attempting to undercut dominant market players is nothing new. But Amazon is in a fairly unique position in that it’s not just competing with these products; in a lot of cases, it’s also selling them via its own platform. That theoretically gives it access to a goldmine of data which could be invaluable if it wanted to launch a competitor of its own.

Amazon was accused of doing exactly this in a Wall Street Journal investigation last year, which alleged that Amazon’s employees “have used data about independent sellers on the company’s platform to develop competing products.” The WSJ specifically cited an instance where an unnamed Amazon private-label employee accessed detailed sales data about a car-trunk organizer from a company called Fortem launched in 2016. In 2019, Amazon launched three similar competitors under its Amazon Basics label.

The same report also detailed an instance of employees accessing sales data for a popular office-chair seat cushion from Upper Echelon Products, before Amazon launched its own competitor.

Amazon tells The Verge that an internal investigation conducted following the publication of the WSJ’s report found no violations of its policies prohibiting the use of non-public individual seller data.

Whether or not Amazon’s employees are breaking its rules, regulators have taken notice. Last year the EU accused Amazon of using “non-public seller data” to inform Amazon’s own retail offers and business decisions. “Data on the activity of third party sellers should not be used to the benefit of Amazon when it acts as a competitor to these sellers,” the European Commission’s antitrust tzar, Margrethe Vestager, said at the time. The Commission has yet to issue a final report or findings, and in a statement Amazon said it disagreed with its accusations.

For its part, Amazon says it has a policy of preventing its employees from using “nonpublic, seller-specific data to determine which private label products to launch.” But the company’s founder and former CEO Jeff Bezos told lawmakers last year that he couldn’t guarantee the policy has never been violated, and sources interviewed by The Wall Street Journal said that employees found ways around these rules.

These accusations have so far centered around low-tech items like bags, shoes, and trunk organizers. But as Amazon has expanded into more areas of consumer tech, its designs are once again straying very close to the competition.

Given these concerns, it seems especially bizarre that Amazon was willing to reference the price of competing smart thermostats sold via its platform during the launch. Its smart thermostat is “less than half the average cost of a smart thermostat sold on Amazon.com,” the company’s senior vice president of devices and services, Dave Limp, said.

Once again, I need to stress that there’s nothing illegal (to my knowledge) about using public information like pricing in order to inform your own products. But taking a moment to specifically reference the pricing of competing devices sold on your own monolithic online store is an odd choice in the midst of all this scrutiny.

It will be impossible to know how closely the functionality of each of Amazon’s new products are to their competitors until we’ve tried them for ourselves. But given Amazon’s size and market power, these kinds of awkward questions need to be asked. After all, Amazon is treading an awkward line between operating one of the largest sales platforms in the world, and competing within them as an increasingly prolific consumer tech manufacturer. It’s a difficult balance, and regulators are watching.